Looking at Ourselves, Looking at Others: “Human Interest” at the Whitney

“Human Interest: Portraits From the Whitney’s Collection,” encompassing two floors of self-portraits, photographs, nudes, and sculptures, asks how one can depict the individual while straying from conventional notions of portraiture. This broad theme is hemmed in only by the limits of the Museum’s permanent collection which, as the scope of works on display demonstrates, seems to limit it hardly at all. With so much to look at, and so many ways to interpret this show, you could visit with a friend and find you’ve seen two entirely different shows.

Installation view of “Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection,” Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Chronology is not stressed here as much as thematic connections, although older works are concentrated on the seventh floor and more contemporary art on the sixth. This thematic organization will be familiar to viewers of the Whitney’s previous permanent collection show, “America is Hard to See.” In the case of “Human Interest”, the themed galleries aim to challenge notions of the genre by creating new classifications of portraits or unorthodox groupings of images.

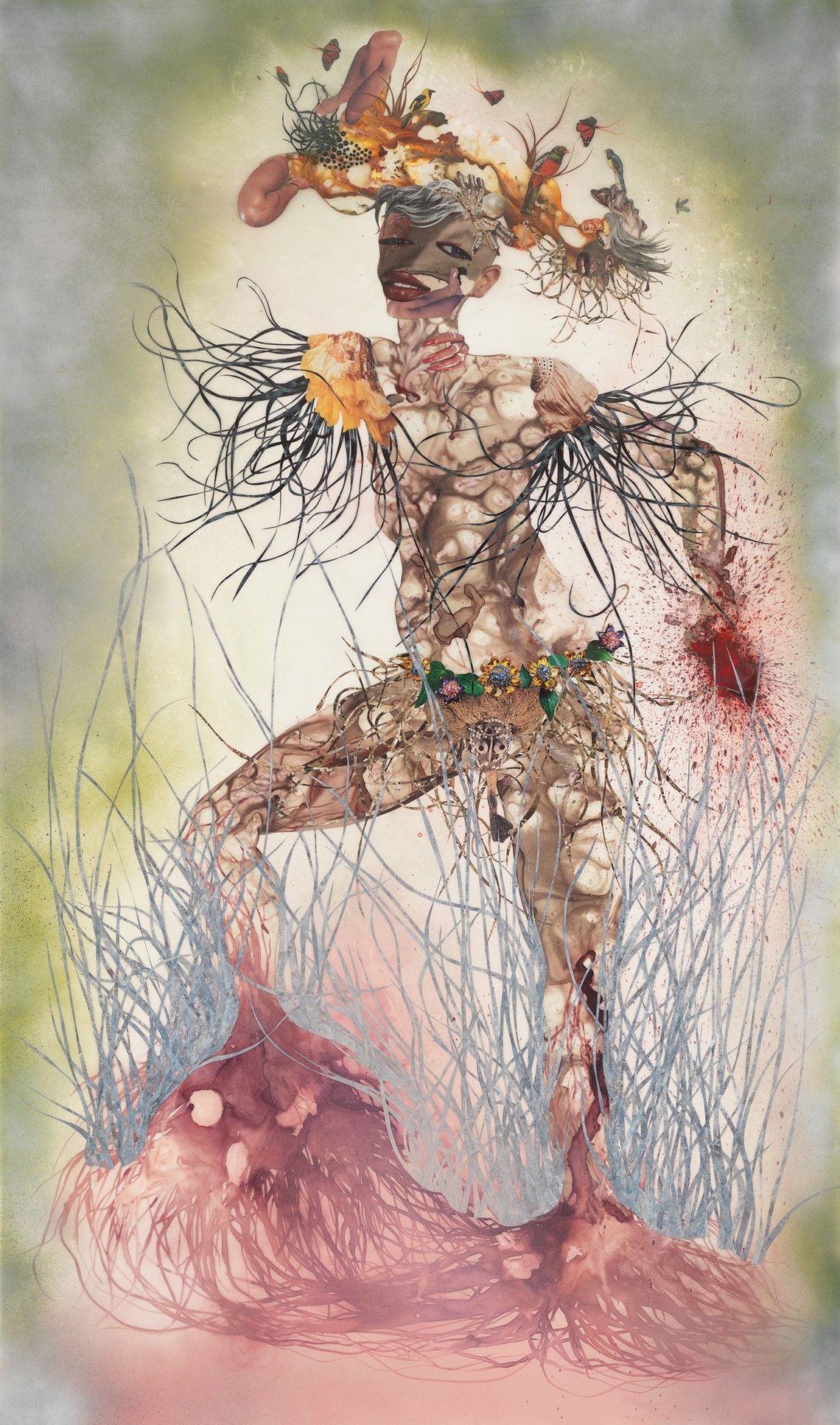

Wangechi Mutu, Me Carry My Head on My Home on My Head, 2005. Whitney Museum of American Art

The Whitney’s curators have interpreted “portrait” broadly, creating memorable rooms that overtly push back against a textbook definition of portrait as physical likeness. I especially enjoyed the gallery called “Portraits Without People,” which explores the non-figural and symbolic ways that artists have represented themselves and their companions. Marsden Hartley’s famous veiled memorial of the German officer he loved and lost to the First World War, Painting, Number 5, hangs here. Some works in this gallery are less clearly non-figural portraits, and the curators don’t provide wall text for every image explaining its inclusion, a lack of context that can prove frustrating. Nonetheless, the gallery succeeds in opening up a conversation about the effectiveness of physical likeness in conveying personality and self.

Another gallery, “New York Portrait,” is an ode to New York City. It plays on the way New Yorkers often consider the city itself a character in their lives. This room includes portraits of individuals, portraits of city types, and portraits of New York itself. One can find Cindy Sherman’s photo Secretary, in which she embodies the stereotype of a young and aspirational administrative assistant, alongside Leidy Churchman’s Tallest Residential Tower in the Western Hemisphere, a painted rendering of real estate developer’s ad for 432 Park Avenue.

Susan Hall, New York Portrait, 1970. Whitney Museum of American Art

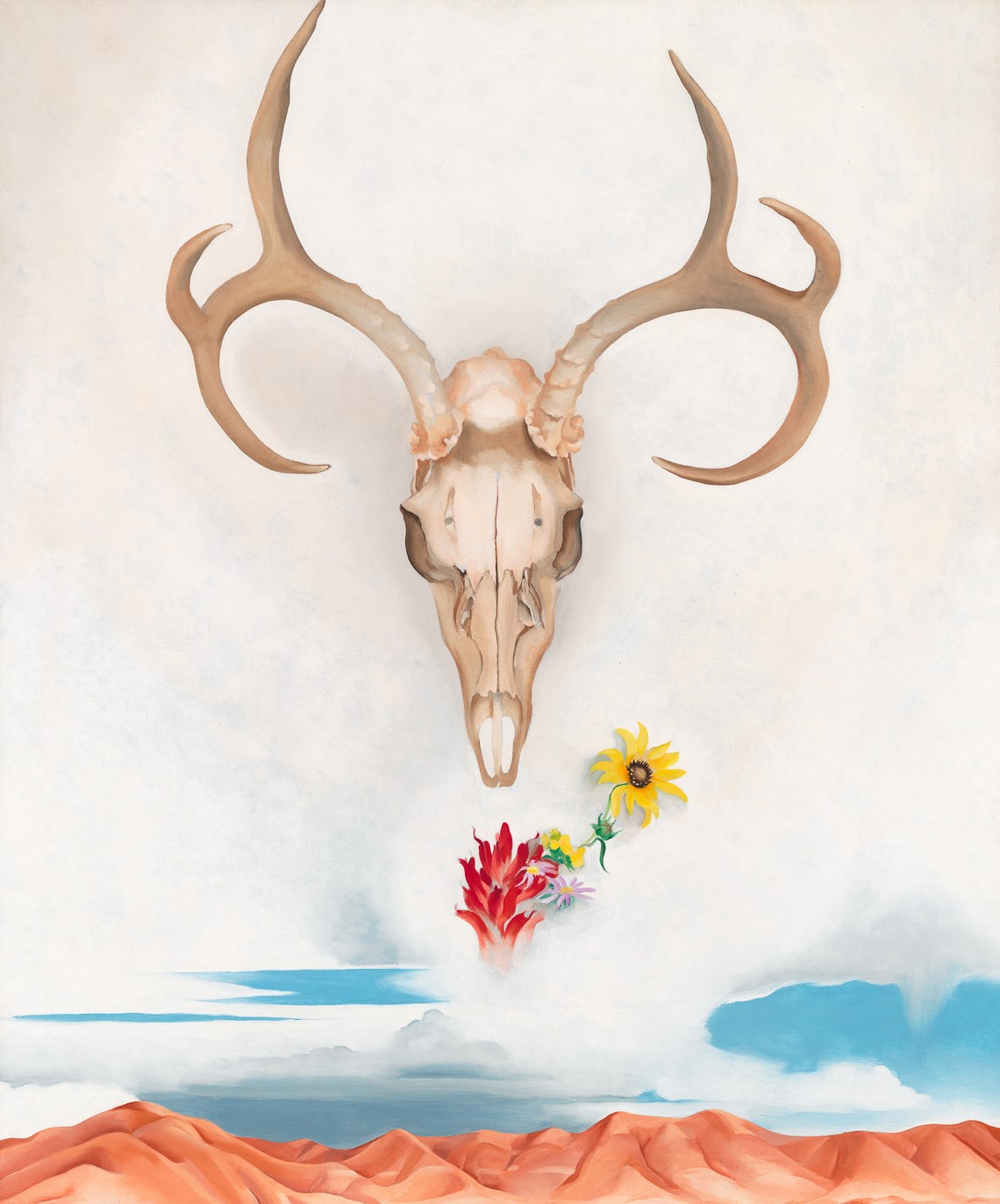

In “Human Interest,” a portrait can be almost anything at all. Georgia O’Keefe’s landscapes are surrogates for the artist herself, and an etching of a sulking Eminem hangs in the same show as a self-portrait by Edward Hopper. The Whitney has worked to make room for everyone in this exhibition and to give every visitor something to enjoy in it. The result is an expansive definition of “portrait” that nearly verges on tenuous but ultimately inspires deeper reflection on how and why we represent others and ourselves.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Summer Days, 1936. Whitney Museum of American Art