Infinity Mirrors From the Inside Out

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., a division of the Smithsonian, launched its most highly attended exhibition ever on February 23rd (over 14,000 people went in the first week!). Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors, a collection of small, luminescent mirrored rooms, curated by Mika Yoshitake, has welcomed the masses to celebrate Kusama’s 65-year-career with a dazzling retrospective. Thanks to my Fordham professor Midori Yamamura, I was able to experience Kusama’s brilliant world of infinity from an insider’s perspective.

I met Professor Yamamura outside the Hirshhorn on the morning of March 9th. An accumulation of red and white polka dots decorated the museum facade with a friendly serendipity. Visitors lined up with iPhones, the seemingly requisite accessories to Infinity Mirrors for the “selfie” generation. The Hirshhorn was buzzing before it even opened.

Yamamura and I were ushered into the exhibition at 9:45 to meet with curator Mika Yoshitake, a friend of Yamamura’s. Yoshitake was finishing up an interview, so Yamamura and I explored Violet Obsession (1994) and Phalli’s Field (1965) for ourselves.

The exhibition opened with a visceral piece: Kusama’s 1994 Accumulation piece, a rowboat and oars upholstered with soft stuffed pillows in the shape of phalluses. The walls were coated in repeating photographs of the rowboat and a warm, eerie violet light flooded the artwork. Yamamura was overjoyed with Violet Obsession’s presentation. I, too, was enamored by the hallucinogenic promise of the exhibition.

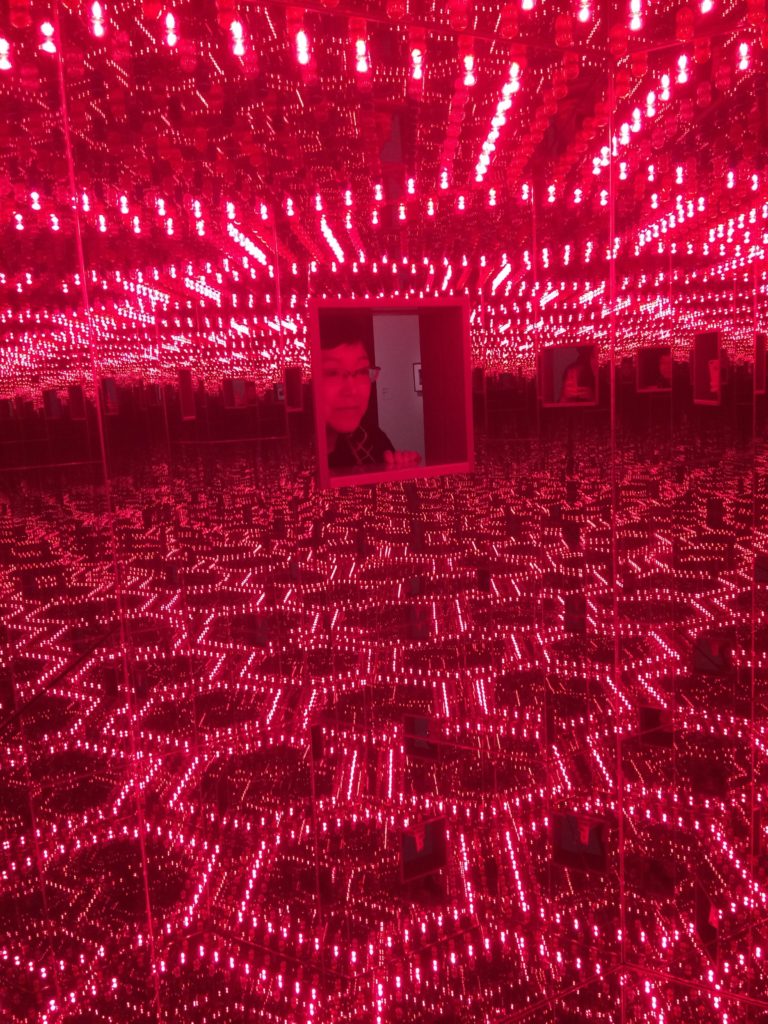

The first Infinity Mirror Room that Yamamura and I entered was Phalli’s Field, a 15-square-foot, low-ceilinged room decorated in red-and-white polka dotted stuffed-pillow phalli. The walls were lined with mirrors which multiplied the phalli infinitely, presenting viewers with an example of one of Kusama’s “visual hallucinations.” Because we were given only 30 seconds to experience the phallic field, I wasn’t sure whether I should be taking selfies to brag about my experience to Instagram, or to stare into Kusama’s obsessive psychosis. With Katy Perry’s notorious Infinity Mirror selfie in mind, I snapped away and then immediately regretted my proclivity for being a self-serving millennial. Luckily, I had five more opportunities to more deeply experience what Kusama scholar Gloria Sutton called the “semiotic relationship between body and space” that the rooms provided.

Yoshitake then joined Yamamura and me. Yoshitake was wonderfully friendly, and she and Yamamura shared hugs and a gift of mushroom miso that Yamamura had brought from Japan. After congratulating Yoshitake on the exhibition’s success, she expressed a note of discontent. Her television interview had gone well, Yoshitake reported, save for the fact that she had failed to meet the interviewer’s expectations, and “make Kusama sick enough.” The curator argued that the exhibition was not about Kusama’s obsessive compulsive and depressive tendencies, but rather a celebration of Kusama’s talent and perseverance in a post-war white male dominated art world.

Yoshitake led us through the ensuing Infinity Mirror rooms, and the remainder of the exhibition. It culminated in an Obliteration Room, which is a white room which visitors cover with different colored polka dots, thus creating a feeling of kaleidoscopic euphoria. She explained that she had designed the exhibition space to be open and uncluttered so as to both highlight and counterbalance the intimate quality of the Infinity Mirror rooms.

Yamamura, Yoshitake and I explored the final Infinity Mirror room, All the Eternal Love I Have For Pumpkins together, and it was impossible not to ask about the infamous “smashing pumpkin” incident. Weeks prior, The New York Times had reported on how a “self-absorbed art fan reaching for the perfect selfie” had destroyed one of Kusama’s LED pumpkins (valued at $800,000) with their selfie stick. The 13-square-foot room was narrow, but it would have taken the most oblivious of narcissists to go so far off All the Eternal Love I Have For Pumpkin’s walkway as to break one of pumpkins. Yoshitake pointed out the pumpkin, which was on left side of the walkway, and the three of us mourned for the selfie-stick generation.

Immediately before entering the exhibit’s Obliteration Room was a wall of Kusama’s latest pieces. At 88, the artist still creates several paintings and sculptures a day, which she demanded be exhibited in the retrospective. Yoshitake explained that Kusama believes that “her work in the last four years is the most compelling; most pressing.” In order for Kusama to allow Infinity Room to come to fruition at the Hirshhorn, she insisted that her My Eternal Soul paintings be included.

Finally, Yamamura, Yoshitake and I entered the Obliteration Room, where we were each handed a sheet of multi-colored polka dotted stickers to place on the walls and furniture. Yoshitake offered that the Hirshhorn’s staff, along with Ikea, had generously donated furnishings and household items including vases and remotes, to be painted white and placed in the Obliteration Room. Suffice to say, I have never felt pure happiness like I felt in Kusama’s Obliteration Room. A gaggle of Catholic schoolgirls were giggling and playing Coldplay ballads on a polka-dot covered piano, visitors were covering themselves and the walls with blue and pink and yellow polka dots. For a few minutes, my fears and neuroses were obliterated by social consciousness and an explosion of happiness in the form of color. “Polka dots are a way to infinity,” Kusama had explained of her affinity. Indeed, her mission to portray the communality of humankind through polka dots had succeeded.

In short, I am incredibly thankful for the opportunity to view Infinity Mirrors from an insider’s perspective. Professor Yamamura is, as always, a warm-hearted wealth of information with a passion for learning, teaching, and sharing. I am so grateful to her for having invited me to accompany her on the private tour of Infinity Mirrors with curator Mika Yoshitake, and for saving me a front-row seat at her panel discussion In Conversation: Kusama’s Path to Infinity with Northeastern professor Gloria Sutton and Arakawa curator Miwako Tezuka.

I would urge EVERYONE to both visit the exhibit (timed passes are available online) and to learn more about Kusama through Midori Yamamura’s 2015 book Yayoi Kusama: Inventing the Singular.

Review by Isabella LiPuma, FCRH ’17. A special thanks to the young scholar, Ezra Rowe Hendler, for proofreading the post.